Review: ‘Hardball’ is brilliant commentary on television ‘journalism’

Napa Valley Register Review by John Henry Martin Aug 7, 2019

Valley Players’ latest production, Victoria Stewart’s “Hardball,” about a young journalist who becomes a right-wing talk show pundit, is a stunningly produced, vitriolic take-down of today’s industry of entertainment journalism. It is yet another winner, cementing Valley Players’ reputation as a serious theater company known for the highest quality production of its shows.

Beverly Wiles Shotwell is Virginia Eames, a young reporter at The Washington Post. In an attempt to prove that the reporters she works with are partisan, despite the directive not to be, she wears a George W. Bush pin to the newsroom, knowing that everyone she works with is voting for John Kerry. The dirty looks she gets proves her point, but she ends up losing her job over the stunt.

What ensues is Virginia’s rise from lowly staff reporter at the Post, to an in-demand talking head who makes a living from her inflammatory opinions. Notably, she is a right-wing pundit, advocating “America First” policies that would be welcomed today on Fox News.

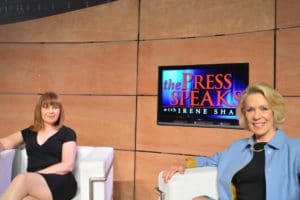

Director June Alane Reif’s vision for the play is spectacular. She, along with set designer and actress Rhonda Bowen, have transformed the stage at Lincoln Theater into a television studio.

The set for “The Press Speaks” with Irene Shay, a fictional political talk show in the play, is right off of CNN or MSNBC with its rich wood paneling and white bauhaus chairs. To make the feel of the studio even more real, three cameras filmed the set when Virginia and Irene would talk, as they do on network TV. You have one camera to get a headshot of each person, then one farther back that gets them both. Monitors on either side of the stage projected each headshot, then a huge white screen above the set showed the group image. Each time a new show came on, stage crews would come out and move the cameras so that they were in frame. It’s a complicated bit of stagecraft that gives the production and authenticity it wouldn’t otherwise have.

The play takes place in 2004, when the U.S. was embroiled in the Iraq War. The crux of the work is when Virginia interviews Suzanne Roth, whose journalist husband Jeffrey Roth is a who was beheaded by Middle Eastern religious extremists on video for all the world to see. Roth’s beheading is reminiscent of 2002 when another journalist, Daniel Pearl, was beheaded by terrorists in Pakistan.

The commentary is that Jeffrey Roth, who is reporting from a war zone, is putting his life on the line for his job, whereas Virginia just spouts whatever sensational soundbite is going to make for good ratings from the safety of her television studio in Washington, D.C. When she insults Suzanne Roth, Jeffrey’s widow, it’s the ultimate in disrespect to his memory.

Virginia thinks she is doing something worthwhile, but really her succession of talk show appearances is just a continuous flow of hot air, nothing that productively advances the political discourse.

A minor, but ingenious, piece of stagecraft in the play was at the climax when Virginia is before a green screen talking to a camera like so many pundits do on cable news shows. The background that you see, isn’t really the skyline of San Francisco or the Capitol building. Its actually an image projected onto a green screen, meant to give some sort of visual backdrop to a bland face. In order to capture the effect that she is going on many different talk shows, the green screen kept changing, in real time, as she would answer a question here or there, denoting a new show.

This scene of the play is also brilliant because while Virginia is making the round of talk shows, her old colleagues at the Post are rehashing her career. The scene is two parallel conversations happening on stage at the same time—a tough thing for the playwright to pull off. Reif’s direction makes the best possible use of the technique, to perfect dramatic effect.

The play is an extremely poignant commentary on an industry that defines our national discourse. People no longer make up their own minds based on facts presented, rather they consume the opinions of professional talking heads who say the most inflammatory things, not because those things are true or valid, but because it makes for compelling entertainment.

From the play, we learn that the fourth estate is not a public service. It’s an entertainment industry that is just as dependent upon viewership as film and television. And the more compelling, or inflammatory the TV personalities are, the more powerful they become, making them celebrities in their own right.